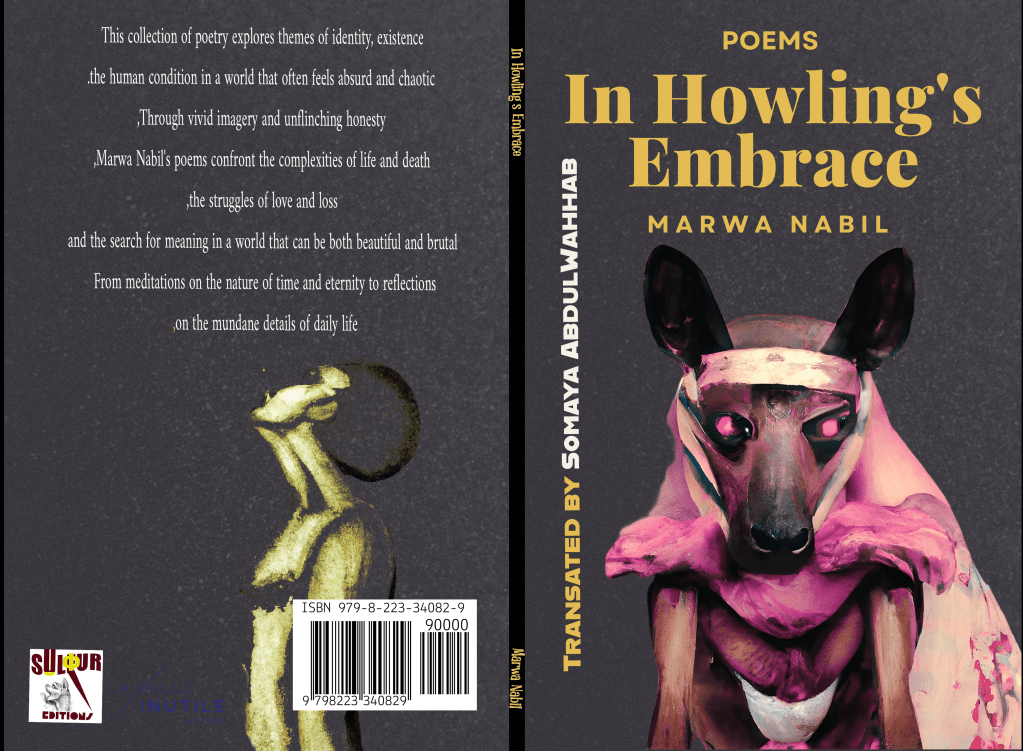

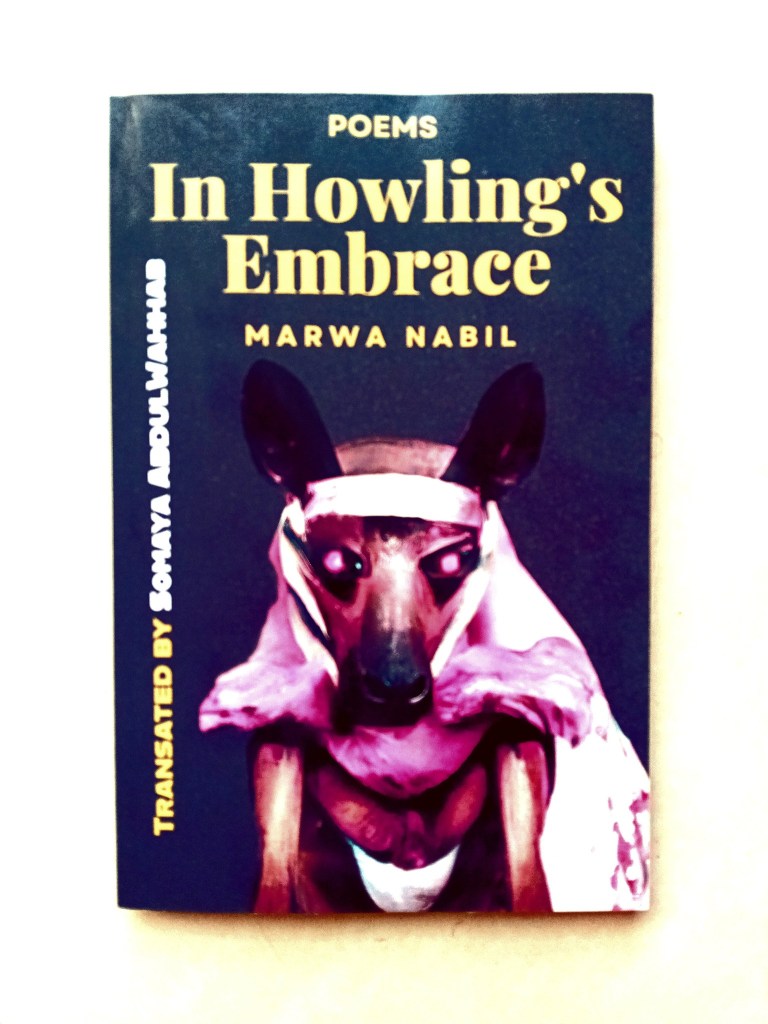

Reflection on In Howling’s Embrace: Poems. Cairo: Sulfur Editions, 2025.John P. Portelli, November 2025

What distinguishes poetry from prose is the fact that it suggests rather than explains. Moreover, the poet constructs reality as she sees it. Her reality may not correspond with the “normal” understanding of reality. And indeed, this is another important quality of poetry. In Howling’s Embrace is a classic example of excellent poetry in the vein of surrealist writing.

“Surreal” is defined as bizarre, unusual, unreal, and “marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream” (via Merriam-Webster). In surreal poetry the focus is not on our reality but the reality of the poet. It may look bizarre from an “ordinary” perception of reality. This juxtaposition surprises us and pushes us to ways of feeling and thinking which we may not have experienced before. But this is exactly one of the virtues of surrealist poetry; it pushes the boundaries of normalcy by giving us glimpses of the conscious and unconscious experience of the poet. Understandably, surrealist poetry utilises a very strong dosage of imagination, and it creates images which may also scare us or, at times, even confirm what we may have experienced but were afraid to express publicly. In this sense, surrealist poetry can be very liberating, not only for the poet but also for the reader.

This collection of poetry by Marwa Nabil is a perfect example of contemporary surrealist poetry. Nabil not only pushes us by her ingenious metaphors, contradictions, paradoxes, unexcepted twists, and her experiences, but she also creates a certain awe and wandering which is very similar, if not identical to, philosophical wonder. Indeed. Nabil is a philosopher and a poet; she cannot be one without possessing the other. She is like the two-headed pictures of the Roman god Janus: two identical faces, one looking toward the left, the other toward the right. But it is the same person. And thus, it is with Marwa Nabil.

Whether or not philosophers believe that truth, reality and facts exist, ultimately philosophy is nothing but a struggle with the very nature of these concepts. Instead of writing a rigid and boring philosophical treatise that only a select few will read, Nabil has produced an exquisite collection of poems in which she mischievously eases out her understanding of truth by focusing, or making us focus, on several crucial philosophical concepts and human experiences. Moreover, she makes reference to numerous philosophers, poets, thinkers, and characters from mythology: Schopenhaur, Buddha, Cavafy, Pessoa, Achilles, Taoism, Hobbes, Rousseau, Heidegger, Kafka, Khidr, Freud, and Nieetzche. She either dialogues with them satirically or she uses them as a solace to her disappointments with the human predicament.

There are several philosophical themes about which Nabil teases us about in a refined poetic manner. She questions whether or not freedom exists, and in a satirical vein she doubts the meaingfulness of the very concept (See, Freedom, 24), yet she seems to support both an epistemology of sensations: “There is no room to speak of organs,/ only a sensation …” p. 45, and an epistemology of love: In “Not a failure” she theorizes about love and reason: “to embrace yourself,/ the very self that knows/ there’s room for love –/ but no reason” p.47. In the poem “I don’t know” she questions aspects of knowledge but yet she emphatically declares: “We are all clusters, and the sky we know/is a shore” p. 49. This is an expression of a surrealist epistemology which is neither realist nor idealist! Maybe Nabil is directing us toward an epistemology of a dialectic.

She also ventures beyond epistemology into moral and political philosophy, where, at times, she hints at a theory of justice: “A poet once affirmed that the world is fair in/all its farts.” 75. She presents a theory of fairnes based on the absurd which is not far from reality given its satricial tone. Like St. Augustine in Chapter 11 of The Confessions,she meditates about eternity and time. She asks: “What is eternity?” p89. In her view, “I shall curse/ whoever calls eternity a sea/ Time, by its very nature is forgetfulness,/ but eternity is not” p. 90.

But maybe the strongest philosophical aspect of this work is what she knows about herself. She seems to take very seriously the Socratic dictum “know thyself.” What does she claim to know about herself? Alot! And this is not surprising given her introspective way of being. Here is a litany of self-declared epistemological claims:

- “For the entire world is within” p. 14

- “I am the living dead. … / and I prefer food in matrimonial games” p. 16

- “I will remain a tiny crown” p.17

- She knows that she is a poet who is “here for the tumult, a fact I know,/ recycling harm./ a ready target, easy to disarm” p. 19

- For the poet the perception of the seasons is constructed as an intrinsic being, referring to autumn she writes: “it is nothing but itself” 32 and that

“it has always been too true to itself” p.33. - “God is not cuckolded” p.51.

- “Things exist, yet they are not truly present;/ and in sleep, all is the same” p.52.

- “To die = to become a feeling earth” p.57.

- Existence is “lit candles on a tray” p. 58.

- “Poetry is a Constellation of Sorrow” p.87

- She knows herself: “I am chaos” p. 54; “I am a monkey” p. 55; “I am a surface” p. 57; “A dragon on a diet turning into a serpent” p. 65.

- “I’ve come to know that all fruite is forbidden/and there are fruits far more valuable than/cheries,/than apples” p. 93.

- “I need something to paralyse this mind;/so I can slip through Eternity” p. 91/2. Her mind is too active; hard to control.

- “I am the existent, the void with my/ speculation,/ I am tha talk of corpses that have surpassed/their meaning” p. 77.

- “As for me, I doubt all colours” p.83.

- “A flying mosquito can halt me” p.100

- “My poems are logical pursuits” p.105.

Throughout the collection she gradually develops a philosophy of relationships, and maybe even of non-relationships. There are several aspects to such a theory. One of the strongest aspect is that of the relationship between love, betrayl and deceit. Notwithstanding what overall seems a bad experience with love, she tells us that “When I am in love,/ my heart tastes like mango” p.60. And yet, in a rather strong ontological declaration, she adds what seems like a tug-of war claim between detrminissm and agency: “You’re doomed to lose whatever you love,/ if existence confronts you, trample it,/ existence is fundamentally against you, and against the daily/mundane” p. 64. Elsewhere she notes: “For there are things that cannot be/overcome” p.88. She accepts a partial determinism. Although such claims sound hopeless, at the same time, she believes that happiness and justice are “a utopia” – an ideal which can never be achieved; even in a surrealist heart and mind and soul? But then comes the blow: “I reach this utopia,/to find only worms, so rife” p. 109. Disillusion, betrayal, false promises. So instead she pleads: “Come to me, my books,/my beloved and my lovers” p.133. And in a very powerful poem, “My poetic carriage” Nabil ends with a lament for the pain of the loss of love. She is also pessimistic about love: “There’s no way to love,” p. 94. Disgusted with the world: “So, I barely write about anything/ but my disgust” p. 76.

Is such a pessimistic perspective justified? Yes, given the poet’s experience of betrayl and deceit. The poet is in search of a genuine relationship but she seems to be afraid of human relationships because of deceit and deceitful love which she compares to a phantom (p.36). She also writes about “betrayal” which she conceives “like a cosmic blow” p.68. And we learn that because of the deceit of love she becomes “a symbol” p. 39. “And my writing about stomach aches/ was what made love” p.84. Love is painful, not easy to achieve. Moreover, Nabil also tells us about the violence so-called love can create: “I am not a rose, to be left to rot in a book,/ I celebrated my body,/I lured it to nothingness,/ and when I sat;/I became a puddle of mud./ My illness is psychosomatic;/I struggle with the horizon, so do not think/everything is in my head” pp. 94-5. Here she starts by lamenting about how her body is treated, I assume as a result of abuse or deceit; then she moves on to make, what most probably, is the strongest existential statement about herself. Undoubtedly, Nabil is also an authentic existentialist. You can trust her through her poetry. The subtext of deceit is very powerful in this collection. She also proposes a response to it. For example, in the poem “My Bed” she writes: “I am a blade,/that kills you smiling/ and leaves you to rot on my bed.” I take this to be a response to the violence of deceit of “the universal fornicator” p. 103. And in the tragic poem, “Desire,” which brings the collection to an end, she bravely reminds us: “You once swore that you detest slim women,/ their lust,/ their vulvas, too./ Yet, your oath guaranteed me nothing” p.144

Notwithstanding the reality of the experience of deceit and the pain of the “last words” (p.40), and “cruel and shame,” (p.41), she believes in the “best word ever” namely “be!” (p.40). And so, she develops other relationships, one of which is with the sea. “There is no sanctity in the sea,/for it requires oil and incense” p.34; but at the same time she declares that “the sea holds no deceit” p.35. The poet has a relationship with the sea which she compares to “a baby metaphor” p.34, and later in the collection, she reiterates “the sea is merely a metaphor” p.61. When confronted by deceit, she also finds solace in philosophy: “I turn to metaphysics to explain my friend’s/ change of heart/ writing my myth as an innocent blue dragon/ exalting glory; licking the ear of a lesser being, believeing/ the latter to be aroused./ They drape themselves in philosophy. Fascinated by Heidegger” p.71. And for Nabil, myth and philosophy seem to go hand in hand, which is reasonable, from a surrealist angle.

Another response to deceit is rebellion. She wears “their neurosis like a badge of pride,” which for her is an act of rebellion; such a statement once again reminds us of the belief in agency. And in her characteristic contradictory voice she writes: “While calculating the mass of nothingness/ that gave me life…” p.86. As she reflects on the human condition she feels that nothingness gave her life, and not love. Maybe love gave her nothingness which, in turn, gave her life! Moreover, she wanders whether “Are all complexities sexual?” p.87. But in her relationships she is very authentic, in fact, “more authentic than the existentialists” p. 89. Yet, her love relationship is turbulent: “A part hates me within,/ it loves you./ Lie next to me/ while I shatter meanings, and you shatter/ me” p. 90; and “I said I love you to nothingness/ and I have turned into nothingness,/harmonised into an existence measured by/the whole (zeros)” p.104.

I cannot end this review without calling to attention to the rich surrealist images and metaphors Nabil creates. Some examples are:

- “Let me alone; I’ll fill void in my faith/with the originally made -in-China sticky/liquid.” p. 12.

- “Inducements; enabling Schopenhauer to/ rent my house,/ turning it into an institute for reforming. Prostitutes,/ guiding them; before he takes his own life” p. 13.

- “When I cry, God dwells in my tears,/ while I become the tissues I dispose later.” Fresh image.

- “Slices of tuna visit me when swimming in dreams” p.62.

There is no surrealist poetry without an emphasis on contradictions and/or paradoxes. And Nabil does not deceive us. Here are some powerful examples:

- “What belongs to God belongs to God,/ yet, deep inside we worship Ceaser” p.21.

- “Satan chants sweetly, and angels steal/ when in need.”

- “My virtue is to end,/and each time I love something,/I kill it.”

In a nutshell, I hope I have demonstrated that Nabil’s collection is a superb example of contemporary surrealist poetry that creatively combines poetry with philosophy, the real with the unreal, love with deceit, betrayal and agency/rebellion. The last word is for the poet herself:

She hints that death kills violence and so she writes: “If I say ‘kill me,’/ it isn’t necessarily a metaphor.” 31. If not a metaphor, then it must be real, no? However, as the poet declares: “Absurdity flows freely,” p.26.

Definitely the best poetry collection I have read in a while! And, by the way, the art work by Ghadah Kamal makes the reading undeniably more enjoyable!

Leave a comment