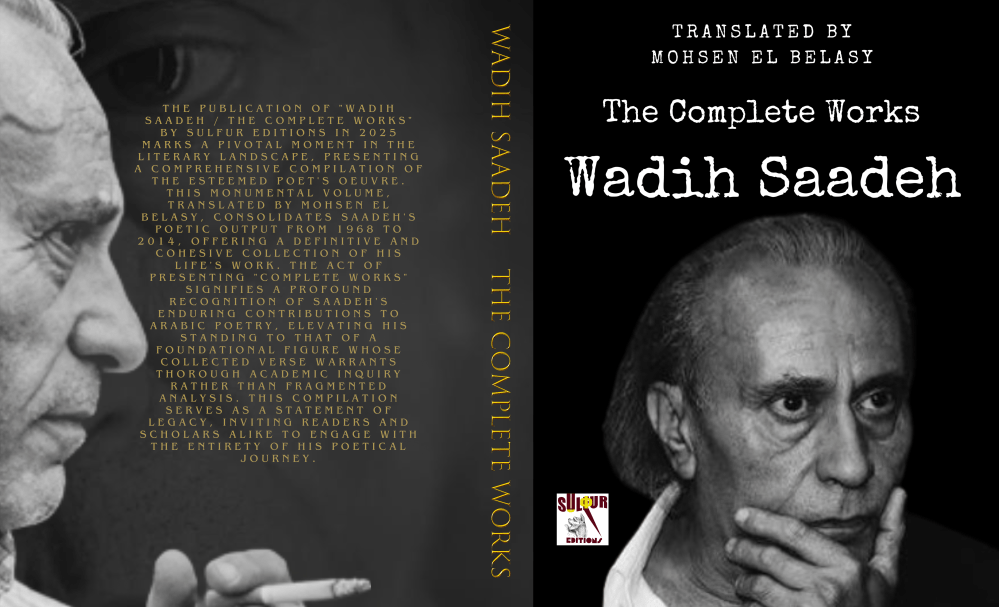

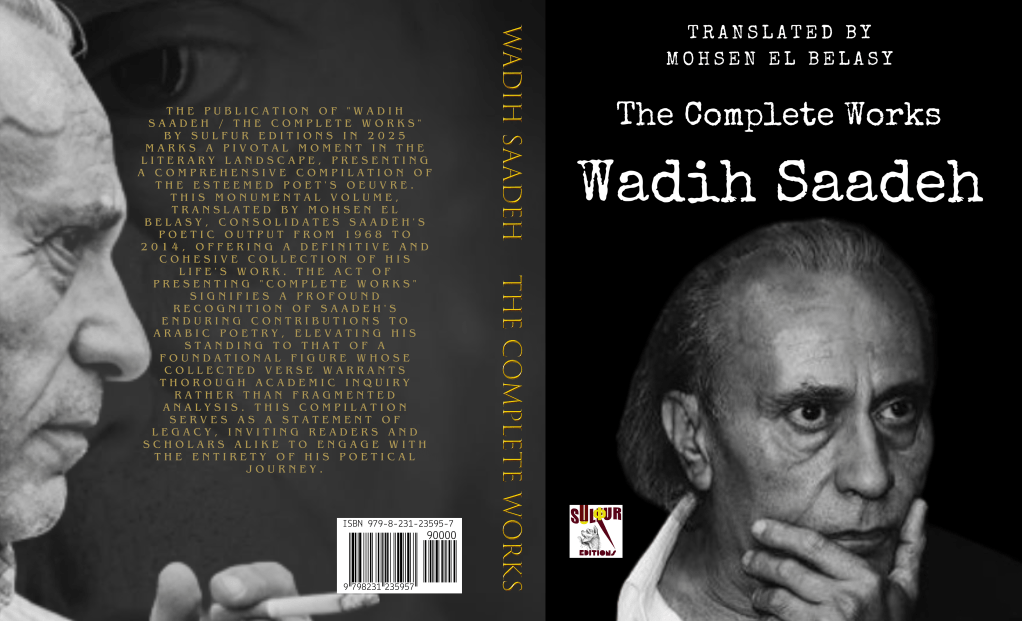

WADIH SAADEH

THE COMPLETE WORKS

PUBLISHED BY SULFUR EDITIONS

The publication of “WADIH SAADEH / THE COMPLETE WORKS” by Sulfur Editions in 2025 marks a pivotal moment in the literary landscape, presenting a comprehensive compilation of the esteemed poet’s oeuvre. This monumental volume, translated by Mohsen El Belasy, Artworks by Ghadah Kamal, consolidates Saadeh’s poetic output from 1968 to 2014, offering a definitive and cohesive collection of his life’s work.

Wadih Saadeh occupies a pivotal position within the trajectory of contemporary Arabic poetry, particularly as a central figure in the development of the Arabic prose poem. Saadeh’s distinctive voice transcends geographical and cultural boundaries, as his poetry progresses from local concerns to an exilic perspective, ultimately reaching an existential plane that resonates not only with Arabs globally, particularly those affected by “repeated loss, violent upheaval and continual disenfranchisement,” but also with a universal readership.

Despite this widespread acclaim and his pivotal role in shaping the genre, Saadeh is paradoxically characterized as an “outsider” within the very history of Arabic prose poetry. This duality suggests that his poetic innovation was not merely an adherence to established norms but a transformative force that redefined the genre itself. His unique approach, marked by a “lack of ostentation” and a personal history of “perpetual wandering” through cities such as Beirut, Paris, London, Nicosia, and ultimately Australia, appears to have fueled this distinctive vision. This personal journey of displacement and alienation served as a crucible, distilling his thematic concerns into universal human experiences. The progression from the “local into the exilic, to reach the level of the existential” indicates that his specific experiences of loss and disenfranchisement were transmuted into a profound meditation on absence, belonging, and the human condition, thereby acquiring a global resonance. This process reflects a meticulous, almost scientific, transmutation of lived experience into profound philosophical insight, solidifying his status as a master whose deviation from convention became the very source of his poetic power.

Saadeh’s poetic universe is profoundly shaped by the concept of absence, a pervasive void that he frequently equates with “nothingness” and even “death”. In his “Text of Absence” (1999), this theme is explicitly articulated, with the assertion that “writing is the absence of life” and that “absence is nothingness and death is nothingness”. This extends to the very fabric of identity, as the self is consistently portrayed as fragmented, elusive, and inherently difficult to define. The Arabic third-person pronoun, “the absent one,” becomes a direct linguistic embodiment of this philosophical concept, representing a “shadow self”. This perspective suggests that the individual is not merely disconnected from external realities but experiences a “total negation” of belonging, being “exiled outside and exiled inside”.

This approach to absence is not a lament for what is missing, but rather a profound exploration of what is when conventional presence dissolves. The idea that creation itself, particularly writing, springs from this void implies that absence is a constitutive force, a fundamental state of being. The fragmented self, or “shadow self,” is not merely broken but perhaps possesses a deeper authenticity in its elusive nature than a supposedly “whole” or fixed identity. This philosophical stance suggests that non-existence or fragmentation may be a precondition for a more profound, albeit unsettling, truth about reality. The very act of poetic articulation, then, becomes an attempt to give form to this formlessness, to map the contours of the void.

Within Saadeh’s poetry, memory is frequently depicted as a weighty and often debilitating force. It is characterized as a source of “misery” and a “burden”, inextricably linked to emotions such as “hatred, revenge, or killing”. The act of remembering is portrayed as a hindrance to both life and death, as it “hinders those who desire death and makes those who desire life, dead”. The past, in this framework, acts as a crushing weight upon the present, preventing authentic engagement with the immediate moment.

Conversely, “forgetting” emerges as a profound act of liberation and a pathway to “happiness”. It is described with the “lightness of flight,” a quality that memory, burdened by its contents, can never attain. Saadeh’s philosophical inversion of Descartes’ famous dictum, “I forget, therefore I am!”, elevates forgetting from a passive state of oblivion to an active, almost defiant, act of self-constitution. By shedding the weight of memory, the individual can shed the burdens of history, inherited identities, and past pains, thereby achieving a state of authentic being. This implies that true freedom and a lighter, more genuine existence are found in a radical detachment from the past, allowing for a continuous, ephemeral re-creation of the self, unencumbered by the echoes of what was.

Death in Saadeh’s poetic cosmology transcends its conventional definition as a mere cessation of existence. Instead, it is consistently presented as a “threshold, an entrance into another realm”. His personas are frequently depicted as “dead, awaiting discovery, ‘vivid with blood and dust,’ yet somehow retaining a sentient alertness to the world”. In “The Dead Are Asleep” (1992), the departed are portrayed as naked, simple figures, still touched by the sun’s gentle care. This perspective extends to the most definitive act of self-termination, with suicides being referred to as “our saints,” individuals who “bestow meaning upon death” and “defeat it” through their ultimate act of erasure.

A crucial element in this understanding is the concept of metamorphosis. Saadeh illustrates this through vivid transformations, such as a drowned person who “became a cloud” and subsequently “fell in drops,” allowing swimmers to “swim in him”. This is not an end but a profound redistribution of matter and consciousness, reflecting a poetic application of the “law of conservation” to existence itself. Nothing is truly destroyed; rather, everything is “rearranged in space and transfigured in shape”. This imbues death with a strange vitality, transforming it into a site of continued, albeit altered, being. The “sentient alertness” of the dead further blurs the boundaries between life and death, implying a continuous, subtle interaction between the living and the departed. This redefinition of death as a transformative process and a site of “sovereignty” represents a profound philosophical move, challenging conventional understandings of finality.

Saadeh’s narrative of “perpetual wandering” and his experience as a member of the “new Arab diaspora” are not merely biographical details but fundamental wellsprings for his poetic inquiry. He explores the multifaceted nature of exile, encompassing both “internal and external exiles” , leading to the profound realization that “the whole earth has become exile” and that “there is no longer a homeland”. This perspective culminates in a “total negation” of belonging, manifesting as an “exile of place and the exile of the other and the exile of the self”. Within this framework, departure is often depicted not as a sorrowful separation but as a “friend” and a “kindness,” even a “rehearsal of the beauty of departure”.

This elevation of exile from a socio-political reality to an inherent ontological condition of human existence is a significant philosophical move. If the entire world has become a state of exile, then the concept of a fixed home becomes an illusion, and wandering emerges as the default mode of being. This is not simply about being geographically distant from a place, but about a fundamental dislocation from one’s self, from others, and even from language itself. The embrace of “departure” as “beautiful” signifies a philosophical acceptance, and even a valorization, of this perpetual state of non-belonging. This re-framing transforms a perceived negative into a source of unique insight and a liberation from the “horrors of being present in the world”, allowing for a deeper understanding of the fluid nature of identity and belonging.

Wadih Saadeh stands as a pivotal figure in the evolution of the Arabic prose poem, a form he masterfully employs as a medium of profound inquiry. His poetic works are characterized by a compelling “mix of brief, orphic riddles and protracted, meditative meanderings” , demonstrating a liberated structure that deliberately challenges the conventions of traditional poetic forms. This choice of free verse allows for a “loose and open” quality in his verse, enabling him to delve into complex philosophical concepts without the constraints of meter or rhyme.

The selection of prose poetry is not merely a stylistic preference; it is intrinsically linked to Saadeh’s overarching thematic concerns. The “fragmented narratives” and “stream of consciousness” evident in his work directly mirror the “fragmented self”, the pervasive “dissolution” of meaning, and the “unsettling and probing uncertainty” that permeates his poetic universe. The deliberate breaking of traditional poetic form reflects a wider dismantling of conventional reality, allowing the very language to embody themes of absence and disintegration. The “protracted, meditative meanderings” serve as a meticulous, almost scientific, exploration of internal landscapes, where the fluidity of the form accommodates the fluidity of thought and emotion. This approach demonstrates a deep understanding of how form can reinforce content, making the medium an integral part of the philosophical message.

Saadeh frequently expresses a profound disillusionment with language, portraying it as a deceptive and destructive force. He asserts that “Speech is betrayal” and “Language is the sounds of the dead”, going so far as to suggest that “When people speak, they grow cold, they fall ill”. In stark contrast, silence is elevated to the “highest degree of speech,” representing “the most eloquent expression of the futility of communication” and “the only celebration available to life”. His contemplation of figures like Rimbaud, who chose to abandon words, implies that silence functions as a “terrifying boundary” but also as a pathway to self-celebration and liberation from the “tyranny of words”.

This valorization of silence extends beyond mere preference; it constitutes a radical philosophical and linguistic stance. If language is indeed the “sounds of the dead” and speech a form of “betrayal” , then silence becomes the only authentic mode of existence, a means to resist the oppressive “tyranny of words” and the “colonies of sounds” that enslave humanity. This perspective is akin to a scientific observation of linguistic pathology: words, in this view, are agents of illness, coldness, and ultimately, death. Silence, therefore, is not merely the absence of sound but a generative void, a space conducive to “internal reproduction” and the emergence of a “cosmos” that truly belongs to the self. It represents a deliberate act of self-preservation and a profound form of communication that transcends the limitations of conventional speech.

A defining characteristic of Saadeh’s poetic style is his pervasive use of paradox and contradiction. His work is replete with statements that defy conventional logic, such as “He said do not approach the water, and drowned”, “Ignorance is the light, and knowledge the darkness?” , and “The slain embraced their killers, so no dead and no living”. These “dialectical inversions structuring his cosmology” are not incidental but central to his philosophical inquiry.

The consistent deployment of paradox serves as a deliberate philosophical method. By presenting contradictory statements, Saadeh compels the reader to question established logic and accepted truths. This technique systematically deconstructs the illusion of certainty, revealing the inherent ambiguities and complexities of existence. It suggests that reality is not a linear or easily definable construct, but rather a fluid and often contradictory interplay of opposing forces. This approach to ambiguity allows for multiple interpretations and fosters a deeper engagement with the “unsettling and probing uncertainty” that underpins his entire body of work. The paradoxes function as intellectual tools, inviting a critical and nuanced understanding of the human condition.

Saadeh’s language is a remarkable synthesis of the poetic, narrative, and scientific, a blend evident in his “precision and tenderness” in conveying “what he felt and sensed”. His poems offer “glimpses into a mind whose preoccupations dwell in the evanescent and the gestural”, utilizing simple, accessible vocabulary to articulate profound philosophical ideas.

The scientific aspect of Saadeh’s language lies in his meticulous observation and precise articulation of phenomena typically considered intangible or fleeting. He examines the “evanescent and the gestural” with the rigor of a scientist studying natural processes. For instance, his detailed descriptions of dust, smoke, or the subtle movements of the wind are not merely poetic imagery but an attempt to dissect and understand the fundamental elements of existence and their transformations.

This precise approach allows him to map the inner landscape and the dynamics of absence and presence with an almost clinical detachment, even as the language remains deeply poetic and evocative. This fusion of precision and evocation enables a comprehensive exploration of complex realities, both internal and external.

The following table illustrates the progression and deepening of core philosophical themes across Wadih Saadeh’s major poetic collections, demonstrating how his persistent engagement with these concepts evolved over his extensive career.

| Collection Title & Year | Absence/Non-existence | Memory/Forgetting | Language/Silence | Life/Death | Exile/Displacement |

| The Evening has no brothers, 1968 / The Evening Has No Brothers – 2 (1973 – 1980) | Emerging sense of loss, lingering void | Time’s decay, memory as burden | Hints of inaudible life codes | Disillusionment, emptiness in pursuit of happiness | Initial stages of wandering, sense of not belonging |

| Waters, Waters 1983 / A man in used air, 1985 / The Seat of a Passenger Who Left the Bus 1987 | Growing focus on void, fragmented self | Memory as burden, desire for release from past | Silence as refuge, futility of conventional speech | Continued disillusionment, death as a state of being | Pervasive wandering, search for belonging |

| Most Likely Because of a Cloud 1992 | Central, pervasive absence, questioning existence | Complex, burdensome memory; forgetting as salvation | Disillusionment with words; silence as purer communication | Intertwined, death as a state; human suffering | Implicit in wandering, sense of not belonging |

| (Text of Absence) 1999 (incl. Dust 2001) | Explicitly central, absence as nothingness/death, fragmented self, total exile | Memory as misery, forgetting as happiness/being | Futility/betrayal of language; silence as highest speech/celebration | Death as possessed/meaningful; suicides as saints | Total exile (place, other, self) |

| Mending the Air 2006 (incl. Another Configuration for Wadih Saadeh’s Life 2006) | Absence as language, nothingness as vast/free space | Memory as burden; forgetting as being/lightness | Questioning language’s truth; writing as prison; silence as reducing enemies | Death intertwined with life/memory; suicides as transcendence/meaning | Implicit in wandering, loss of physical boundaries |

| Who Took the Gaze I Left Before the Door? 2011 / Tell the Passerby to Return He Forgot His Shadow Here (2012) / A Feather in the Wind (2014) | Ephemeral existence, fleeting traces, pervasive solitude | Memory is burdensome, past manifests in the present | Silence is as profound/valuable, the futility of speech | Mortality, intertwined with life, desire for release | Isolation, desire for liberation from the burden |

Saadeh’s poetry consistently elevates seemingly mundane elements, such as “dust, clouds, soil, and other amalgamations of particulate matter.”

—into profound symbolic vehicles. These transient substances, in their “fragility, their tendency toward dissipation,” paradoxically embody a remarkable “endurance”. Smoke, for instance, transcends its physical properties to become a “privileged medium of clarity”, while dust is transformed into a fundamental state of being, as articulated in the declaration, “The earth has become dust, and here we complete the life of dust”. Similarly, water is depicted as a transformative agent, capable of metamorphosing the drowned into clouds.

This intense focus on ephemeral, everyday elements is not merely descriptive; it constitutes a profound philosophical statement. By imbuing these transient substances with deep meaning and endurance, Saadeh suggests that the grand narratives of existence—the cosmos, life, death—are intimately reflected and contained within the smallest, most overlooked details. This approach mirrors a scientific inquiry into metaphysics, where the inherent properties of matter, such as dissipation and transformation, become potent metaphors for ontological states. The “fragility” of these elements is presented as the very source of their “endurance” , a compelling inversion of conventional understanding. This perspective invites a reconsideration of what truly constitutes substance and permanence in a world often perceived through fixed categories.

Saadeh’s poems are populated by recurring archetypal personas, predominantly male figures, who are often “seized while sitting on porches, departing from houses, clipping a sunbeam”. These figures frequently exist in a liminal state, often depicted as “dead, awaiting discovery, ‘vivid with blood and dust,’ yet somehow retaining a sentient alertness to the world”. The “sleeper on the sidewalk” is another recurrent motif, embodying a state of detached observation and quiet contemplation. The poet himself often adopts the role of an observer, even of his fragmented self, lending an introspective quality to the narrative.

The consistent deployment of these archetypal personas, particularly the “dead” who retain “sentient alertness”, establishes a unique narrative perspective. This allows Saadeh to explore themes of presence and absence from a liminal space, blurring the conventional distinctions between life and death. The “observer” persona, whether living or deceased, facilitates a detached, almost scientific, examination of human experience, stripping it of sentimentality and revealing its raw essence. The fluid, shifting gaze—from living to dead, from present to absent—is a deliberate narrative choice that reinforces the philosophical fluidity of existence, where identity is not fixed but perpetually transforming. This technique enables a multifaceted exploration of consciousness and being, extending beyond the confines of a single perspective.

Saadeh’s poetic style is characterized by “fragmented narratives” and a “stream of consciousness”, where events are glimpsed rather than fully recounted. This stylistic choice is particularly evident in the numerous short, aphoristic statements that comprise collections such as “A Feather in the Wind”. The poems trace “autobiographic tracings” and focus on “evanescent and gestural” moments, prioritizing internal journeys and perceptions over external plots or linear progression.

The fragmentation of Saadeh’s narrative is not a stylistic deficiency but a deliberate artistic choice that mirrors the “devastated” reality he frequently portrays, a reality marked by “war and the deep internal and external exiles”. A linear, coherent narrative would, in this context, be a betrayal of such a disrupted experience. Instead, the “brief, orphic riddles and protracted, meditative meanderings” offer fleeting yet profound glimpses into a mind grappling with a reality that resists easy categorization or conventional understanding. This fragmented approach actively invites the reader to participate in the construction of meaning, reflecting the subjective and often disjointed nature of memory and perception in a world characterized by “continual disenfranchisement”. It is a narrative strategy that embraces the inherent brokenness of experience, transforming it into a unique form of poetic truth.

Saadeh’s Poetic Devices and Their Philosophical Implications

| Poetic Device | Example from Works | Philosophical Implication |

| Paradox/Contradiction | “He said Do not approach the water, and drowned.” | Deconstruction of certainty, revealing inherent ambiguities and the fluidity of existence. |

| Metaphor/Simile | “Language is the sounds of the dead.” | Embodiment of abstract concepts, revealing the futility of conventional communication and the destructive power of words. |

| Personification | “The earth is blind, give it an eye so it sees you.” | Imbuing inanimate objects with sentience, highlighting the subjective nature of reality, and the human projection onto the world. |

| Aphorism/Fragment | “I spoke much, but silence was my only treasure.” | Concentrated impact, reflecting a disjointed reality and an embrace of silence or non-action as a form of being. |

| Repetition/Anaphora | “I forget, therefore I am!” | Redefinition of being, emphasizing cyclical thought and the pervasive nature of certain ideas. |

| Use of Third Person/Absent One | “The absent one” | Embodiment of absence, reflecting the philosophical fluidity of existence and the self as a “shadow self”. |

| Linguistic Innovation/Neologism | “He nothinged Moses” | Pushing the boundaries of expression, enacting philosophical concepts through the very structure and invention of language. |

A fascinating aspect of Saadeh’s legacy is the nuanced manner of his influence on subsequent generations of Lebanese authors. While his impact is undeniable, the writing of these newer voices often “grows apart from the war-marked imagery of their predecessors”. This suggests that Saadeh’s influence transcends mere imitation of content. Instead, it lies in his pioneering efforts to liberate poetic form and to deepen philosophical inquiry beyond direct political or historical inner trauma. His “unrelenting, quiet discontent” and profound focus on internal states provided a foundational framework, enabling later generations to forge their distinct voices while still building upon his innovative contributions to prose poetry and existential contemplation. This demonstrates a legacy rooted not in replication, but in the empowerment of diverse artistic expression.

Saadeh’s body of work has been characterized as “monumental works of postmodern nihilism”. However, this designation does not equate to a simple expression of despair. Rather, his poetry was conceived as a “kind of salvation” and a “momentary, illusory cure” in confrontation with a “perpetually antagonistic world”. The “dialectical inversions structuring his cosmology” suggest a profound transcendence of conventional binaries. In this framework, loss is transformed into a “precondition for vision,” and smoke, typically an obfuscating element, becomes a “privileged medium of clarity”. His exploration of “dark themes” is not merely an articulation of suffering but an active philosophical engagement, striving to unearth a form of liberation.

The understanding of Saadeh’s nihilism as a “momentary, illusory cure” implies a therapeutic or transformative function, rather than a purely destructive one.

Wadih Saadeh’s poetry, deeply rooted in his personal experience of “exile and alienation”, undergoes a process of “purification and distillation” that imbues it with “universal implications”. This transformative quality allows his verse to speak directly to “Arabs across the globe of this generation disaffected by repeated loss, violent upheaval and continual disenfranchisement,” while simultaneously resonating “to all of us”. His later works, in particular, function as “thought experiments, staging grounds for distilled aphorisms and propositions”, thereby transcending specific cultural or historical contexts.

The process of “purification and distillation” of personal experience into universal themes stands as a testament to Saadeh’s poetic genius. His willingness to delve into his own “memories, his fears, and his attempts to assuage them” with an “exquisite attention” to his “inner landscape” creates a profound connection with the reader. By meticulously focusing on the “evanescent and the gestural” within his mind and body, he taps into fundamental human experiences of loss, longing, and the search for meaning. This approach allows the intensely personal to achieve an infinite, universal reach, demonstrating the powerful interplay between the poetic and narrative dimensions of his scientific inquiry into the human condition. The intimate becomes the gateway to the infinite, allowing his unique voice to echo across diverse experiences.

GET THE PAPERBACK COPY NOW FROM BARNES& NOBLE/Click the image

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/wadih-saadeh-the-complete-works-wadih-saadeh/1147737971

GET THE E BOOK VERSION FROM BOOK 2 READ

Leave a comment